Episode 10: Security in Space with Schuyler Towne

What challenges does physical security face in outer space? Would it be possible to pick a lock in space? Join Emily, Alexa, and their guest, historian of security Schuyler Towne as they discuss how the history of security may help inform the security of the future.

Show Notes:

Schuyler Towne

Youtube:

Transcript:

[Intro Theme: “Space” by Music Unlimited]

Emily

Hello and Welcome to the Art Astra podcast. I’m Emily Olsen.

Alexa

And I’m Alexa Erdogan.

Emily

And we’re finally back for our second season of the show. Thank you to everyone who’s listened to our previous episodes.

Alexa

We have so many new and exciting episodes we cannot wait to share with you, including this one!

[interlude: “Space” by Music Unlimited]

Emily

So today we have a wonderful guest with us. Schuyler Towne is a historian and anthropologist of security technologies. He was an early fixture in the American locksport movement, known for co-founding The Open Organization of Lockpickers (TOOOL) U.S. chapter and launching Non-Destructive Entry Magazine. As a research scholar at the Ronin Institute, he proposed a new theory for the origins of the keyed lock, worked to recover patents lost in the 1836 U.S. Patent Office fire, and wrote extensively about the Great Lock Controversy of 1851. Schuyler is a sought-after speaker and educator, having given talks and workshops at dozens of security and technology conferences and institutions such as MIT, Princeton, and Olin College.

He has also provided consulting for various books, games, and television productions, and moderated several panels on hacking and entry on film at the Tribeca International Film Festival. Schuyler, thank you so much for joining us today. Welcome to the show!

Alexa

Yeah, thank you so much, Schuyler.

Schuyler

Thank you so much for having me. I'm genuinely quite excited.

Emily

Yes! We are, too! So first off, right out of the gate, how did you get into the American locksport movement? How does one become a competitive lockpicker?

Schuyler

For sure. I didn't intend to whatsoever. I didn't grow up picking or anything like that, but I did grow up obsessed with hackers and hacker culture. I played sports. I loved music. I enjoyed TV and movies, but none of my heroes were like actors, musicians, sports people, anything like that. I was just early on the internet, early on computers. I remember lugging my dad's quote unquote portable IBM computer up the stairs to my bedroom when I was too small to physically lift it. So I had to do it step by step, bashing it on every step. So I was, yes, obsessed with The Cult of the Dead Cow and L0pht Heavy Industries and all sorts of other things that will ring bells for, I don't know, anybody listening to this maybe, but certainly a bunch of people that I know nowadays. And when I was in my early 20s, some friends reached out and they had also been into this when we were all kids, but they went on to have wonderful and well-paying careers in computer security or computer engineering, computer anything. And I went off to a theater school instead. But they said, “You know, we're going to this hacker conference. We used to read about them when we were kids. Why don't you come along?”

So we loaded into a car, went to the Hackers on Planet Earth conference in 2006, and it was extraordinary. They brought me to a talk on lockpicking that I had no interest in, and to be perfectly honest, I kind of thought they were big dorks for being excited about. But the guy giving the talk was just wonderful, just an absolutely incredible guy. His name was Barry Wels. He was the head of The Open Organization of Lockpickers. He'd founded it in the Netherlands. He's a Dutchman, and he's very soft-spoken on stage, but it was like he was doing these little magic tricks. It was a very basic talk. His wife sold me my first set of picks later that day at their little lockpicking village they had. And I bumped into him in the lobby, said, “This thing you're doing is incredible. Is there anyone doing the sport picking here in America?” He said, “Come to this thing I'm doing tomorrow. I'll tell you all about it.” And I showed up.

He introduced me to three other people who very clearly did not know me or why I was there.I didn't know why I was there. And then he opened up his arms and said, “You four are my new board of directors for my American locksport organization.” So it's an exciting sounding credit in that very nice bio that you read, but it really just happened because I was very polite and he took a shine to me immediately.

So he had me out to Holland three months later, my first time picking internationally. I spent my last dime on the plane ticket, so he put me up with his family. He drove me up with his family. I have pictures with his kids in the backseat of his van on the way up to the actual competition venue. And yeah, I won half my head-to-head match as my first time ever competing. Came back to America, won the American Open out in Las Vegas at DEFCON, the massive, largest annual hacker conference in the world, came back, won a new competition there hosted by Deviant Ollam, who actually took over for me on the board of TOOOL later that same year.

He's phenomenal. He'd created this incredible, like, spectator sport that he called the Gringo Warrior. At the time, you had to get out of handcuffs, get yourself out of a cell, retrieve your passport from a filing cabinet, so on and so forth, and eventually defeat a door lock and an auto lock. So it's a great mix of locks and confinement and so on and so forth. So yeah, that first year in Vegas, I won the speed competition. The second year I won Deviant's new competition and got to know this incredible community of people, started teaching, won the Locksport Wizard Competition back at the next HOPE that I got to attend two years later, back at the place where I learned all of it to begin with.

That was hosted by Doug Farr, the president of Locksport International at the time, another American locksport organization. And it was just this incredible, vibrant thing that was happening in America all of a sudden that we had imported, thanks to Barry and some other folks from Holland and Germany before that.

But yeah, literally I just...I was nice to a guy and he took a liking to me and invited me in. I had truly, literally the best lockpickers in the world as my teachers when I first got starting and I had a knack for it.

Emily

That's so cool. Ending up with like a trajectory of locksport based off of someone you meet at a conference is just like the dream, honestly.

Alexa

Yeah.

Schuyler

Yeah. Well, and that totally can be how people get in today still. And plenty of people have gotten in because they've, yeah, bumped into me at some lock picking table that I'm running at some random conference now. And they've had the chance to introduce them to it. And they've gone on to be exceptional at it even. But the luck of Barry Wels coming into your life, I think that's a little rarer these days.

Alexa

It sort of sounds like it wasn't just the interest of lockpicking itself, but also the community that you found yourself with really kept you like entranced by it and kept you moving forward in it.

Schuyler

100%. And in fact, the first talk I ever gave in what would become a prolific speaking career for a few years of my life was just titled “Locksport: An Emerging Subculture.” And all it was was me talking about all the cool people I had met.

[laughter]

Schuyler

It was just saying, you know, “It emerged out of Germany. Let me tell you about these amazing German lockpickers and this incredible story of the culture of locksport there, how it moved to Holland, Barry Wels, all of those amazing people I've met and who's doing exciting things here in America now. It was truly just like…

It was almost like my report on what I did over the summer. It was such a joy. Yeah, first talk I ever gave at any of these conferences as well was truly just about that culture because the community itself was extraordinary. And even though I don't pick competitively anymore, and I don't know, charitably I would say that I take long periods off from the community, but I'm kind of always coming back to it. There are individuals that I know in it now, but I'm not steeped in it the way that I used to be. But God, I really did love it. Yeah, the people and the competition, those were the things that really drew me in deep and quick.

Alexa

Mhm. Touching on the projects that you've done in terms of like speaking and also writing, I can't help but my curiosity wants me to kind of go back to the bio a little bit. There was something in there about a “Great Lock Controversy of 1851,” and I have been dying to ask you about this because this sounds fascinating. Can you tell us a little bit more about what this controversy is?

Schuyler

Yeah, it takes very little to get me talking about it a lot.

[laughter]

So the Great Lock Controversy of 1851 is this really important watershed moment in the history of not just security engineering, but security culture. It becomes this moment of divergence between British and continental Europe security culture and American security culture in some really interesting ways. And it all started about 80 years before that. I could very enthusiastically talk to you about this and only this for the next few hours, but the tidiest version of it I think I can come up with is:

There was an incredible lockmaker named Joseph Bramah. He made his fortune designing a really good toilet and then continued his fortune by making the first fire engine, like water-pumping fire engine. He died after contracting pneumonia while demonstrating an insane hydraulic tree-uprooting machine that could uproot fully grown trees straight from the ground with hydraulics. He was really good at, yeah, hydraulics. But also, he designed one of the most important locks the world's ever seen. And clearly, I lied about this being the shortest version of this. I just told you way too much about this one man, and there's so many more involved.

[laughter]

But Bramah in particular, I've described him before as like a wizard from the future that just happened to show up in England in the 1770s, 1780s.

One of the really amazing things that you'll find over and over again, I'm sure in any history of science, history of technology, are people who know what the next thing should be, but the technology doesn't exist yet to actually create it. And Bramah is a phenomenal example of this. So in the 1770s, early 1780s, he's noodling around of this idea that eventually becomes the Bramah safety lock.

Without going into too much detail about exactly how it works, the short of it was it needed to be so incredibly precise, and the components all needed to be exactly the same every single time, and the tooling just didn't exist to create it. So eventually he meets this guy Maudsley. Maudsley's a young dude. Bramah was a pretty young dude himself, but this guy was, I think, literally a teenager when they first met. And he was brilliant at making tools, dyes, specific forms, to help with his vision. So the two of them got together, made the Bramah safety lock, absolutely brilliant lock.

We can relatively comfortably cut forward to 1851 now. There's one other development that happens. Chubb, Jeremiah Chubb, as a response to a competition that was being held by the royals to find a lock that could alert you to an attempt on it. So it would have to alert the user to somebody having tried to pick it. So Bramah's detector lock comes about in, I believe, 1911. So these two locks, from the time of their inception, independently, effectively remain unpicked this entire time. Now Bramah in particular had an issue early on where a locksmith figured out how to pick the Bramah safety lock within the first year or so that he was on the market with it.

He accepts that this has happened, adds a really simple feature called a serration to the individual tumblers in his lock, which completely obviates the method that this locksmith had used to pick it. And to reassure everyone that his lock was now safe, he starts this challenge. So he puts in the window of his shop, the Bramah Challenge Lock. And the Bramah Challenge Lock, from sometime in the 1780s, I forget the exact year that the new model gets put out there after the initial picking attempt, through to 1851, nobody successfully opens the Bramah Challenge Lock.

Chubb, his lock in 1911 – phenomenal detector lock. Nobody, maybe, opens his lock. There are many more rumors of his being opened, some of which seem pretty solid, but no public openings, no big competition openings. Bramah's lock in particular gets a ton of challengers and a lot of really interesting challengers, and Chubb’s does as well. Bramah's in particular, though…

The terms would typically be that you would have like 30 days to work on this thing. And Bramah's version of this challenge winds up being taken up by other manufacturers of other locks and even translates across the ocean to America, where this dude, Alfred Charles Hobbs, A.C. Hobbs, is starting to make a name for himself in the lock-making world. He's partnered up with Day and Newell, a company out of New York. He's going to be a salesman for them. He also contributes some mechanical engineering to their product generally. But in particular, he's an incredibly talented lockpicker. And the way that he sells their locks is he shows up to one of these competitions, he picks the lock, he sells them a Day & Newell. Does this over and over and over again. Now, as I said before, typically pickers were given like 30 days to work on these locks with long periods, sometimes even unmonitored periods of time with the locks.

And this is what he would wind up having with the Bramah safety lock. But in America, he starts opening these locks in 20 minutes, 30 minutes. So all of a sudden, what he is able to do has compressed the impossible time to open some of these amazing locks that are coming out around this time really, really dramatically.

So, Crystal Palace, the Great Exhibition of 1851, Britain showing itself and its colonies off to the world, all of the industries gathering in England, big, year-long event in a gorgeous setting, and Day & Newell send Bramah out to promote the Day & Newell Parautoptic Lock. And to do this, Bramah intends to pick the only two perfect locks in the world.

Now, genuinely, the British believed in the concept of perfect security. You can follow it through their literature and so on and so forth. And someday you can either read my never-submitted-to-anyone pilot, which is much more fun to read, or a really long paper breaking down all of this stuff, whatever floats your boat. But it'll take you through all of the reasons that I really earnestly believe that the British believed that perfect security existed and Bramah had found it. The Americans, we didn't believe that. And this culturally is where this division starts to take place in our security cultures.

So Alfred Charles Hobbes rolls into England, almost immediately manages to pick a Chubb lock, almost immediately manages to pick a detector. Doesn't take terribly long in the grand scheme of things. Within a few days of being there, he picks one for the first time and people are there to witness it. Chubb and Chubb's sons, the family Chubb, freak out about this. They're not into that. And as a result, they demand like a more formal challenge, one that would be adjudicated by actual jurors and so on and so forth. So that goes through, picks it again, 100% definitely picked the Chubb lock clean, done.

And the way in which he does it, one of the very…(Again, I lied right at the outset. There's no brief version of this for me because I like it too much. I'm so sorry).

[laughter]

But just a fun little artifact of all of this is that if you actually read an encyclopedia entry in one of the amazing British encyclopedias from back in the day, I wish that I had the author's name to hand right now, but I don't. But there's a man that writes the article about locks, and in it, he proposes picking the Chubb lock in an encyclopedia. He describes how it would probably work, and it's literally exactly what Hobbes rolls in and does. Effectively, the mechanism that detects the person picking it detects it at a very specific point.

So every time you feel the detector fire, that your true position of the key would have been ever so slightly lower, like ever so slightly lower. And so Hobbs just dialed that in. He figured out how to unset the detector. So he would just let the detector tell him what the actual key would have been, unseat the detector, dial in the correct positions of the tumblers, and boom, have it open very quickly. In fact, when he did this in front of jurors, he initially took, I think, let's call it 30 minutes to open it the first time in this more formal setting. And everyone's like, “Oh my gosh, I can't believe that.” And he was like, “Yeah, check this out.” Picked it locked, picked it open again in like 12 minutes this time, picked it lock, picked it open again in about 7 minutes this time, and was just showing that this method, this method had it solved. This lock was a solved problem. The Bramah safety lock, on the other hand, a much harder proposition. So very cool.

His attempts on the Bramah safety lock take place over the course of, oh, I used to have these numbers down, but it has been a moment since I've talked about it. I think it was about maybe 34 days, 52 hours, or I'm mixing that up and it's 54 and 32. Regardless, a remarkable amount of time, longer than it has ever taken A.C. Hobbs to pick any of the locks that he has picked. And he has to revisit it routinely, take tons of measurements, have a ton of time with it alone, design specific tools that can manipulate it.

There's a big controversy, hence the name, going back and forth in the papers. So Chubb is writing letters to the editor. Well, Chubb's family, Bramah's family, Joseph Bramah, you know, long passed at this point. But these lock-making houses, yelling and screaming in the papers about, what's right, what's wrong, so on and so forth. And Hobbs himself more than happy to jump in and excoriate them for their behavior and so on and so forth. But eventually it does get open. And once it's opened, he was able to effectively create a key for it. And he was able to demonstrate that he was able to open it consistently. The original key still functions for it, which was one of the stipulations that he hadn't just broken it in order to open it.

And he was awarded the prize money for that one. And the British papers at the time are tearing their hair out, ripping their shirts, wailing in the streets. Some of the writing about this is really beautiful. One that I loved may have been from the Times or The Illustrated News of London. Again, it's been a minute since I've talked about this formally. But the author said, you know,

Schuyler

“It seems cruel at this time of day that when men have been taught to look on their bunches of keys with something of a sense of security, to scatter that feeling to the winds. We thought that Bramah was as secure as Gibraltar, or even more so, for we took Gibraltar, something, something” and begs, begs the British lock-making public “to go and pick that damn Day & Newell lock, design another perfect lock, so on and so forth.” But in the end, perfect security dies.

It dies on that day, even though the Bramah withstood such a completely unreasonable length of attack. Like, nobody today would consider that anything less than perfect, really, because we kind of know that perfect security doesn't exist. But genuinely, there is this belief in it. And the knock on to this...And the cultures of the two larger communities becomes really interesting.

And again, we could talk about this and nothing else, but I'm excited to talk about space and other things.

But in particular, like this is a very small thing. Okay, so in America, let's say you leave your house completely unlocked, you go off to the store, somebody comes in and takes a bunch of your stuff. They still broke into your house and burgled you, for sure. The insurance would pay out. There would be charges, so on and so forth.

In England, if you didn't lock your door, you would potentially be responsible for that having happened to you. That is a real oversimplification, and that is not universal across Britain. But that same idea, there are places that will do that. [laughs] There were stories that I was reading about where a police officer would just like try someone's door, find out it was unlocked, and let their insurer know.

In order to get insurance for your home, you have to have locks of a certain security standard. The security standards body has to issue it between like one and three stars, and there's all sorts of like really useful stuff in there.

In America, there is a standards body that validates high security locks, but only high security locks. Insurance companies have no say in what type of lock you use on your door or potentially if you use a lock on your door. You might get better rates, discounts, etc for like adding alarms or using a security lock. There are ways to incentivize it, but just culturally there is this like need for high quality mechanical security as part of the social contract versus the sort of law and social norms as the core of the social contract.

And God, I'm like terrified to say that on a podcast because there's so much more nuance that should go into it, but I'm going to leave it at that because I've been talking for way too long. Oh my God.

[laughter]

Alexa

No, that's fascinating. And as you were talking about that too, it's like, I didn't even think about the fact that there could be different cultural perceptions on locks and security and how much that bleeds into everything else in our society. And it also makes me think about international collaboration of space and security. The blend of all of those cultural perspectives on security is really interesting. And space is a unique place to explore that, especially.

Schuyler

Absolutely, especially as India are getting to space now and more in there, because there are some incredible security traditions in India. And obviously it is a massive and diverse country with so many different pockets, but there's like a deep handmade lock crafting culture in many parts of India. And at the same time, there's this very interesting sort of social rejection of mechanical security and security norms in areas as well. Like a dream of mine would be to someday spend like six months in this incredible city called Shani Shingnapur, where people live without locks, like full stop.

Even the… a branch of a national bank wanted to come into town and just culturally, they wind up having to get sort of permission to just be staffed and guarded around the clock because the community wouldn't tolerate them having locks on their front door for the bank.

And to my knowledge, they're the only like large and modern community in the world that lives without locks, and they've done so for many generations. Most live without doors, in fact!And they'll have curtains drawn across their living spaces, and they have amazing cultural traditions around community, security, being watchful for one another, being watchful of one another, so on and so forth. Just absolutely incredible and contrasted with massive, like massive lock making, like tiny, small industry, but geographically dense lock making industry throughout other large swaths of India and exporting a ton of locks as well. Really, really amazing mix of traditions in that country.

Emily

That's fantastic. And we'll be sure to also be including links in our show notes for listeners to also look into these, because I know that we're going at kind of a clip, but all of it is just so cool.

So having studied the history of security and the culture of security, is there anything that surprises you about security today, either physical or digital?

Schuyler

Yeah, for sure. I think one of the big ones, I don't necessarily even know if it's a surprise or just sort of a simmering, unending frustration is the frequency with which we see physical, mechanical security used as metaphor for digital security. And I don't just mean in like explaining a product or so on and so forth, but like literally in case law.

It makes absolute sense that as we try to grapple with the technologies that keep us safe online, in our electronics, digital tools, so on and so forth, that we rely on metaphors from the physical world. Makes absolute sense, but at the same time, things really start to fall apart pretty quickly.

For example, ages ago now, I was working with an incredible lock picker. His name was John King, and he had invented a tool called the Metacoder.

Metacoder was super cool. It turned out that he had effectively landed on a parallel technique to somebody else much earlier, but unsurprisingly, a lot of…especially attack design and tool design in the security world doesn't get a lot of record keeping, doesn't have a big cultural impact, and people wind up reinventing that particular wheel over and over again.

So he, however, was part of my generation of hacker, lock sporter, et cetera, and he wanted to do something about it and tell someone about it and not just sell a tool to an agency and make a buck and move on with his life. So once he had the tool locked in, basically it worked against an amazing high security lock called the Medeco Lock.

It could very quickly help you set the high security feature of the Medeco lock. You would then still have to pick it like a normal pin tumbler lock, but it would have defeated the very, very good high security feature of it. Incredibly clever tool. He made it like in his apartment. He made a lathe out of a drill that he turned upside down and put in a vice. [laughter] It's a terrible idea, but it worked out for him. He survived, and had accomplished his goal.

[laughter]

But he reached out to me and said, you know, “I'm not quite sure what to do next. I know that you know some folks.” So I reached out to a wonderful guy that I had met through Barry Wels and the European locksport community, who was the head of R&D at Medeco at the time. He was kind enough to meet with us. I drove down to Virginia to get together with the two of them.

John demonstrated the tool, validated that it worked. And Peter Field, sorry, was the name of the man from Medeco. And Peter revealed that, “Yeah, like once we saw what the design was and it was described and detailed to us, we were confident that it was going to work. So here's what we've done so far. Here's what we plan to do to mitigate this going forward,”... so on and so forth. And part of the conversation that John and I had ahead of time was, you know, what does responsible disclosure look like in the physical security world?

And it worked out really nicely, honestly. Peter Field wound up co-disclosing with us, published a paper to the locksport community that was really lovely, kind of like welcoming us into the fold of the tradition of security engineering, which was really nice. They had a fix out for it, took the time to get the machines running and the parts made and so on and so forth. So we held our publication for a little while, so on and so forth.

However, even with it all having gone perfectly, my guess is approximately zero of the affected locks were ever actually repaired. The reason being that when you talk about patching something in the digital security world, hopefully the devices that you're dealing with are connected to the Internet, you can push something to them. Yes, people don't always update. Yes, people ignore it, so on and so forth, but you can at least get the patch on their doorstep.

You can at times force them to stop engaging with something if they don't update. You can simply force an update nowadays as we go along, so on and so forth. With disconnected devices, they might lose some functionality over time. There might be an opportunity when somebody like physically carries a device into a place to say like, “Oh, and I updated your firmware because we know about this bug,” or whatever the case may be.

Nobody walks around with the lock to their front door. It is immovable. It is effectively as transient as your home. In order to patch the lock, somebody has to physically come out, physically disassemble it, physically add a new part in, physically reassemble it. It is outside of the realm for most basic users. The tools involved have, at times, it needs simpler to service your own locks, but in general, it's never going to be, you know, “Download this. Install it. It'll take care of itself.”

There are so many more examples and some really terrible ones when it comes to sort of personal privacy and federal investigations and so on and so forth where they talk about physical locks and we should effectively rule on digital security the same way that we would with like coercing the combination to a safe out of someone.

But these are such incredibly different physical realities. They're such incredibly different paradigms of security and the risks involved and the scope of risk involved are so incredibly different from one thing to the other.

So yes, I think pretty much not a single one of those locks actually got the patch, effectively, that Medeco came up with. Well, I would say statistically 0, right? Some did. Some definitely did, because some of us got a kick out of it, and ordered the parts kit and made the swap ourselves.

And importantly, additional locks coming off the line after that point, after that inflection point, did have the fix, like they had committed to that. That's a wonderful thing. But there were hundreds of thousands, millions of locks in service that were susceptible to this attack.

But another really important difference here: no one can sit at their computer and write some code and press a button and carry out this attack on the high-security lock on your front door. That's another big shift, right? So in general, I think that's the thing that really surprises me, that we still don't seem to have gotten past this point of really relying on our understanding, knowledge, and metaphor of physical security technology to describe, understand, litigate, and create laws around digital security. And I think that there’s some fundamental dangers there. We need to tell the stories of digital security in its own terms.

There's a lot of cool overlap in behavioral security, a lot of wonderful things we can learn from those physical world metaphors and how people behave and engage with security. But we're enough generations into securing ourselves on our devices and online that we truly need to do this work on its own merit and based on its own reality, not coming from the mechanical security world anymore.

Emily

I'm also thinking about, in terms of your example of you can't take your physical lock with you, so much of work today is built around being able to remotely access things. And in order to allow that access, you're also including more vulnerability to something that you wouldn't necessarily have if it was physically locked the way that it would like your front door.

Schuyler

100%. The attack surface of a house is measurable. The attack surface of you jumping on a Zoom meeting from your cell phone at a coffee shop is likely literally immeasurable. Yeah.

Alexa

It's such an interesting perspective too, when you talk about physical and digital locks and the accessibility to upgrade and improve upon both sort of genres. And I'm curious what your perspective is on how those challenges for each kind and even also including the context of space itself, how do those challenges translate to outer space or what is it about outer space and the outer space environment like space stations that create sort of unique challenges for physical and digital locks…?

Schuyler

Totally.

Alexa

…Or security in general.

Schuyler

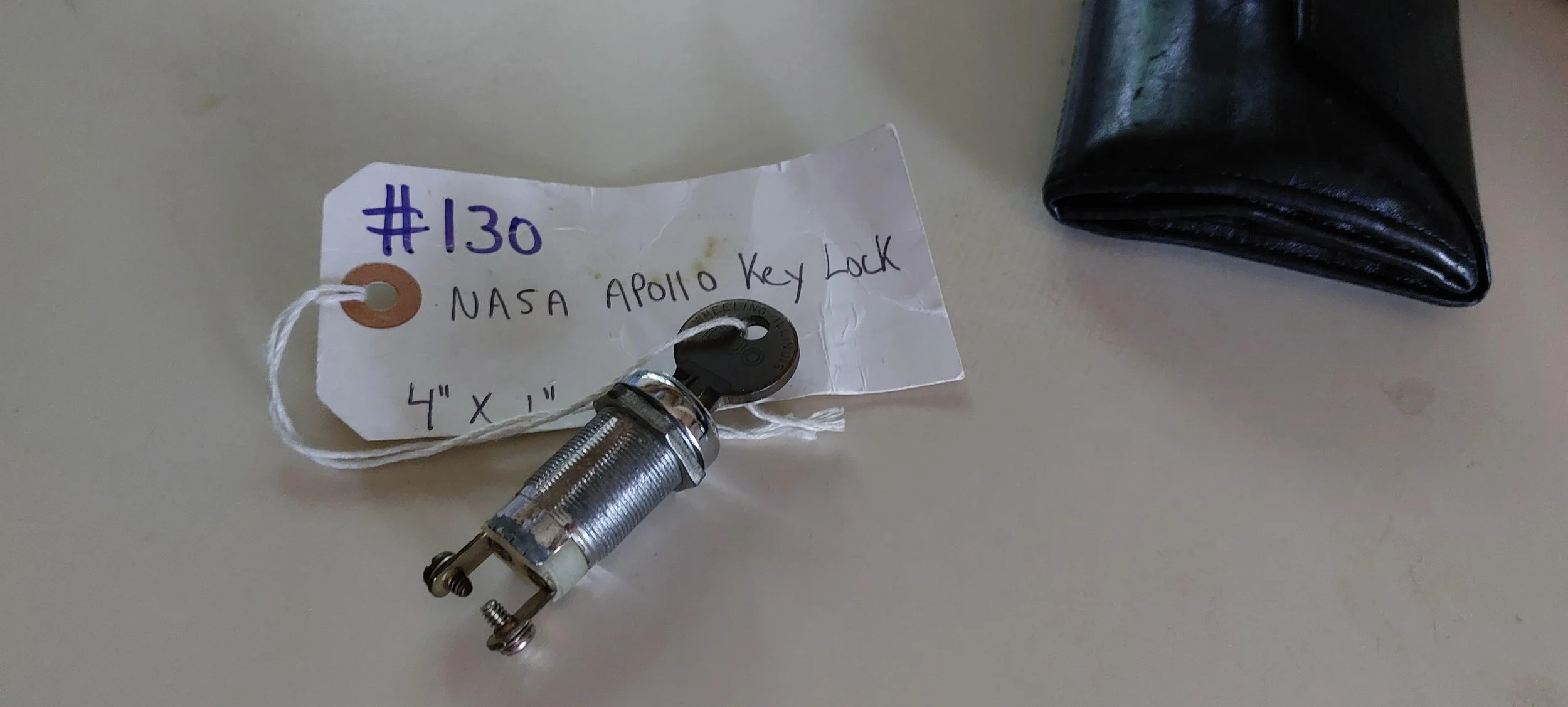

Yeah, I've been very excited to get to start noodling on this since y'all reached out. And also, I brought along something that I thought you might get a kick out of, which is we already have locks in space, such as this wonderful lock from an Apollo [capsule] that I have in my own little lock collection here.

This one, this very specific lock did not go to space. And as a result, it was so incredibly affordable compared to all of the things that did go to space.

A lock with key from an Apollo capsule. Image courtesy of Schuyler Towne.

[laughter]

Schuyler

100% up to date on y'all's own podcast and really enjoyed the auctioneering of space. And yeah, oh my goodness gracious, you know, no lock nerds in that particular auction. And thankfully, this thing didn't go to space. So I was able to get my hands on it very affordably.

But truly, it's cool just to think about like, if humans are exploring space, we have to have locks. I don't know what all we will encounter. And I have said on stage once, in fact, while being interviewed by Joshua Foer, founder of Atlas Obscura in Connecticut, the very first time I ever said yes to Joshua Foer, and I learned to never say no to him. He put amazing opportunities in front of me. He was interviewing me on stage, and I feel like out of the blue, he asked me like “What I would ask an alien?”

And I just said like, “Do you have locks? Like, do they exist for you? Do they exist?” And the reason being was that I had truly come to understand locks, or at least some form of like administrative security technology, and I'll break that down in a second, but some form of that technology, locks being the most common, as a fundamental building block of humans forming societies larger than their own family units.

Schuyler

I'm backed up in this by the brilliant [Abbas] Alizadeh, who is a phenomenal archaeologist working out of the University of Chicago, who wrote a long time ago that door sealings, so these amazing clay tablets, that would be used to seal off doors to limit who had access to a given one.

He said outright that door sealings, in his estimation, can be taken as the first signifier of a society, of a move from tribalism to actual society. Because as you begin blocking off public, private, and semi-public spaces, you begin defining the ways in which people are allowed to gather, how they're allowed to move through space, who they're allowed to be in community with. And it blew my mind. It blows my mind right now. This is a thing I know and have been saying for a decade, and I'm like a little goosebumpy about it. [laughter]

So yes, I initially, as I began thinking through locks and space, I couldn't help but think about Star Trek, not so much Star Wars, not that there isn't stuff in there, but some of it's more recent as we've seen like heist genre in Star Wars becoming a thing now with Rogue One and Solo and so on and so forth.

But, you know, Star Wars was always like old serials, right? It was always super, super genre.

Star Trek has a lot of people moving through space and hierarchy and so on and so forth, but it also has this sort of post-scarcity utopia beauty to it. And so most spaces are transited without any trouble. And it becomes this extraordinary thing if somebody has closed themself off, which is interesting and great for storytelling and so on and so forth.

But in general, I realized that my inbuilt idea of locks in space was, "Well, maybe we don't have them. Maybe this is what our post-lock society turns into." But of course, I realized that like, yeah, in my basement, I have evidence that we have locks in space right now.

[laughter]

Like we went up there and brought locks with us because of course we did. Because locks are this fundamental administrative technology of society and of social order.

And so long as society and social order continue to exist, we're gonna use locks to administrate those spaces to facilitate movement through those spaces, so on and so forth. Now there are interesting things within that, like what kind of locks are we gonna have in space? What… what does that look like? What are security cultures of, you know, multi-generational space-dwelling human beings look like? I'm fascinated by all of that. What will the security culture of the first colonized planet look like, if it's a British colony versus an American colony versus an Indian colony?

Like truly tying right back to what we were just talking about, that we already terrestrially have these incredibly diverse security cultures that already exist. And what we will bring to space is ourselves and our social structures and our social norms. And so many of those are backboned by security technologies.

I think one of the really amazing things, as a matter of fact, as we've become more intertwined, more connected to each other, and it's funny because I truly often think like a historian, and in my mind I was thinking, you know, as we so recently have become more intertwined – I'm thinking many hundreds of years [laughter] ago.

The concept of a shibboleth, of a word that someone in a community pronounces in a particular way, and so that when outliers from that community are moving back into physical spaces inhabited by other people that pronounce that word in the same way, they can literally say the word, say shibboleth, and be known to be part of that community and culture, even if they don't have a direct familial relation to them.

So this idea of the shibboleth is ancient, of course, and real, incredibly real. But to me, the really remarkable thing is that we've always needed that historically, societally, etc. And we still have that in many ways, right? You catch somebody with a similar accent to your own and you get interested and excited to learn a little more about them. You hear about somebody that went to school up in the place that you're from and you want to talk about those physical places, the people maybe you knew, so on and so forth.

I'm a 13th-generation Vermonter. We predate the country up there. And as a result, there's some weird, deep, inbuilt cultural knowledge that I have that occasionally I bump into somebody else that has, and everything else kind of drops away and we come together on this strange, deep, old cultural tie. Whatever else maybe separates us, and I'm a bit of a whackadoo, and so I'm really separated from them on most other things. But I can hang for a moment on that cultural piece, on that sort of layered shibboleth of our shared history.

But as we start to make this transition from communal familial spaces to private and sometimes even commercial spaces, and then this really fascinating middle ground, which is the semi-public or the semi-private space. As the semi-public and semi-private spaces came into existence, we needed a new shibboleth because suddenly we were going to have people who did not necessarily share an accent having to share space and having to know that each other were in community with one another.

And today, if you are able to successfully key fob in to a semi-private building, you pull out your key fob, you tap it on the reader, you open the door, you walk in, that physical card is your shibboleth to the community that you've just walked into. By demonstrating that you can be physically present in a semi-private place, that you have the credential to be, that is your shared cultural connection. The key is the modern shibboleth.

You don't need to speak the same language, much less have the same accent for pronouncing a particular word, to have the same, in that space, cultural context as someone else because you both have access to that space.

Now, there's some very cool stuff in attack design that actually takes advantage of this, where instead of trying to get your way into a single door, the goal is to create the key, to create the physical key or the fob or whatever the case may be, because you're not just trying to gain entry, but you're trying to gain the authority of entry, which is its own amazing thing in attack design and lockpicking and entry and so on and so forth, all of which is very cool.

But, here's what I am confident about when it comes to space: The resources that are required to get any significant group of people that you could consider a society into space are going to be so extraordinary that they are going to inherently be in a semi-private space. That might be cordoned off into separated areas, so on and so forth. But what will have to happen is that we will carry those same social, cultural, and administrative technologies, like locks, along with us.

The person that can gain access to the physical space that you have is of your community, whatever scale that might be, when we're traveling through space together in a large enough community to be considered a society.

Locks will be with us in space, of that much I'm confident. Exactly what they'll look like, what locks terrestrial could make that transition I have thoughts about, but I know they'll be there with us because we're going to create society anywhere we go. And locks are the inherent technology of society.

Emily

I have so many follow up thoughts on that specifically, because I've been thinking about the Apollo lock you showed us and how if it's in a capsule, like the crew is 3 people.

Schuyler

Right? Yeah.

Emily

Because the other thing too is with what you were talking about with how you're thinking in terms of centuries, but the space age is not that far away from present day. Actually, I looked up as we're talking, this is the 50th anniversary year of the Apollo Soyuz Test Project…

Schuyler

Wow.

Emily

…which would have been the first time in which technical geopolitical enemies are connected meaningfully in the same space.

But even before that, in terms of talking about shibboleth as an example, like the cultural differences we're talking about in terms of what an Indian space culture would look like. And even in the ISS today, you've got like the Russian section and the American section and how obviously everyone can move throughout it, but there's still these delineations. And then on top of that, we have, in terms of what we're talking about of the people being physically in the space, having their own community, however small, it actually… In a previous episode, we were talking with a space archaeologist, Justin Walsh, and he was talking about how there is actually very little privacy when you're all in such a confined space together for such a long period of time. And so I'm just fascinated by like what that lock would even be a part of in the space capsule.

Schuyler

Absolutely. And this lock, I'm, I'm relatively confident only because of the format that was put into that this lock was to validate an action that somebody wanted to take, which is another wonderful service that locks provide us. So this lock would connect to an electric switch and could only turn that switch on if the key was actually turned correctly.

So locks are this wonderful social administrative technology, but they also, in their myriad forms, like the fingerprint identification on your cell phone, offer us this form of… sort of constant validation of the action that we want to take as well. So there are these personal, like human technology mediating devices as well in a really cool way.

Like locks as an administrative technology, whether on the person to person, person to culture, person to architecture, or person to technology, the lock is always an administrative technology in how it allows us to, yes, validate a decision, identify ourselves, transfer across space, so on and so forth.

So yes, in this case, I think that this lock, not as much, despite my exciting and flowery words before, about the delineation of society, but about the validation of choice.

Emily

Going back to lock picking and in terms of physical breaches of security in a space environment, but even just like a zero gravity environment, it's so funny because I'm literally thinking about lock picking, and how I'm picturing someone doing it in astronaut gloves, which would be so difficult…

Schuyler

SO hard!

Emily

…because the manual dexterity would be such an issue.

But out of curiosity, I think it would still work. But as the expert guest, would conventional lock picking still work in a zero gravity environment? Because I think that pins might get stuck...

Schuyler

So theoretically, yes, but as you point out, the lock itself, sans gravity, will behave a little differently, but not necessarily massively differently. So the big move away from gravity-driven locks to spring-driven locks happened around the 1500s, not universally, but this is where, especially coming out of like a African-European tradition, we see the spring start to be introduced.

And then, eventually cut to the early 1900s in Finland, we start seeing springs fail, as it turns out.

They were wonderful for making sure that we could mount locks in all sorts of places. We were never able to mount them when we were gravity dependent and made more portable and so on and so forth.

But springs can also fail, and space is a shockingly brutal environment in reality. There's interesting questions about like how do magnetic locks fare outside of an atmosphere. Even those, usually like the solid magnet is in the key and then the parts are just ferrous or whatever.

But it's interesting to think about these like spacefaring failure scenarios and all of those. Regardless, as far as actual lock picking is concerned, whether you're picking against the spring or whether you're picking against something like a disk detainer lock, and disk detainer locks are my vote for our spacefaring locks, if anybody is listening and I get to provide any influence.

In particular, there's a great line of locks: the S&G Environmental. What I like about them is that they're used at like northern rail yards where they're going to just be out in the frozen permafrost for a year or two before anybody needs to open them again. And they work.

And a big part of why they work is there are no springs. They are dead simple. You could stuff them full of dirt and then just shake the dirt out of it and the key would still go in and work just fine. Locks like that, locks that are designed to work in extraordinary environments terrestrially, I think are a great bet to work in the extraordinary environment of space.

But my big question is, and I don't have a great answer for this: what's it going to feel like to pick in zero g? What's it going to feel like when the sensations of your own body are so out of sorts that you still need to see through your fingers. Truly, lock picking really is visualizing something inside of the lock through what you feel through your fingers. It is absolutely seeing through your fingers, as silly as that sounds.

And the best example I have for this, and kind of my best guess, is picking underwater. So a guy that I mentioned, Doug Farr, wrote for me in Non-Destructive Entry Magazine about doing diving and lockpicking while actively diving. It was something that he was excited to try.

He did it. He wrote a wonderful piece about it in Non-Destructive Entry Mag back when that was a going concern. And it was a hoot. Potentially there is some utility for it. I can't really imagine, but you can certainly…when you get to be a very good lock picker, you get to have a really rich fantasy life about exactly what sort of James Bond scenario you're going to be in as you're picking the hatch to the Russian sub in the middle of the Atlantic or whatever.

[laughter]

And Doug was right there with it with the fantasy. But a very cool thing that Doug did was he brought this experience to the rest of us with a really fun competition that took place at the Hackers On Planet Earth conference in, I think it was 2008, but it might have been 2010, one or the other.

But he created these amazing watertight, like treasure chest looking stations. And he would have head-to-head picking with a big watertight box for one picker and a big watertight box for the other, a bunch of padlocks locked inside, and then the water level slowly rising.

No! The water…Ah, I don't remember where the water level was at, but effectively there was a button that you could push that would flood the other person's compartment.

The reason I remember this is because I happened to get paired with a child, like probably an 11 year old child.

[laughter]

Schuyler

And what I would love to say is that I know that you had to press that button to flood the box because that kid just kept pressing that button flooding the box.

[laughter]

But in truth, I got so angry at how hard it was to pick underwater that I was just spamming that button to flood his stupid box because he was beating me so handily.

[laughter, wheezing]

Schuyler

I had just won. Like the day before, I had won this amazing blindfolded lock picking competition called the Locksport Wizard Competition. Wonderful competition, also invented by the brilliant Doug Farr. And I was really feeling myself, and this 11-year-old took me to school.

[laughter]

Schuyler

But picking underwater, so I think they, yes, I think what it was, they started flooded and they would slowly drain, and then you could add water back into your opponent. But he could do it. You should have him on the podcast to talk about lockpicking in space, probably. I'll track him down.

[laughter]

Schuyler

But I couldn't believe it. I couldn't believe it. Truly, it felt like more so than the blindfolded lockpicking competition that I had won the day before, it took my sight away. It was amazing. Picking underwater, I had no idea what was happening in the lock anymore. My senses were just gone. Yeah, really, like, internally took that sight away from me completely. I genuinely don't know if I used appropriate language with this kid. I hope I did.

Schuyler

But people were dragging me for a long time about how clearly actually angry at a child I got.

[laughter]

Schuyler

He was great. I think after I finally lost, I calmed down and congratulated him.

[laughter]

But yeah, in the moment, I'm a fierce competitor. But yeah, so that's the only thing I have to compare it to. And it worked out terribly for me. So I shouldn't be… I shouldn't be first in the shuttle for whatever James Bond space lockpicking mission we have lined up.

Alexa

On the plus side, you may have inspired that kid to become like the first lockpicker in space or something.

Schuyler

God, I love it. In the comments, let us know.

[laughter]

Alexa

Actually, as you were talking about that, it made me think about how everything is so interconnected, especially when it comes to space. If there are different type of lock designs that eventually we have to create once we get more like interplanetary as a species, I wonder if that itself will have an impact on like how we're designing our spacesuits.

And Emily, you were saying like astronaut suit gloves - I can't imagine doing like basic tasks in that, much less something that requires such fine control. I wonder how that sort of interaction between spacesuit design and locks is going to play out, too, in the future.

Schuyler

Like let's imagine that yes, you have to transit from one vessel or one habitation to another, and you have to do it in an environmental suit. How do you, and you know, take this step of imagination one step further, like, and this is a common enough thing that we have to know who's in the suit, that they're allowed to come through this door, and we can't always do it, verbally, code words, so on and so forth.

Like at some point we have to replace the shibboleth because this is just a common thing, a border that needs to be crossed over and over and over again. I think there's some interesting stuff in suits themselves, having an engagement with some sort of port so that you are potentially having a biometric identification within the suit, and then the suit transmits some information into whatever it is that impedes the progress at the door.

You know, my guess would be that we're going to be living in that sort of realm of interesting sci-fi design, more so than we will in like really whacked out spacey biomechanical lock designs, but I think that's cooler.

[laughter]

Alexa

Space steampunk.

Schuyler

Yeah, of course. But, you know, I think the reality is the technology that we are, I mean, right now you already have, like, it's not an environmental suit, but very frequently now, and speaking to what you were saying previously, Emily, about how there are so many layers of just like basic going to our work and doing our job, like layers of interesting security between here and there that happen. And very frequently, our phones are the in-between for that, right?

Like our phone will accept the pin, the password, or the biometric data that validates that the correct person has the phone. And then the phone validates to whatever the system is that, yes, we're here signing on, doing the more complex math in the background to gain access, right?

I just truly, I imagine that that environmental suit, if that's the situation that we wind up in, having to transit from one space to another, one vessel to another, that that same workflow that feels really boring already [chuckles], just toss it up into space in a slightly different form.

And this is one of those places where I do think that, so this is that important distinction again, right? Seeing how we engage with our phones as a security technology, not just us accessing the phone, but the phone itself having become this token system for us in so many ways, that flow of behavior, that path that we potentially have, that we can now map on to a new scenario, so on and so forth, super useful in designing those technologies and experiences and behaviors around using that technology in the future in a new context.

Terrible, however, to use whatever laws maybe we come up with right now about how we can use our phones to access things and then map those on to some person in a space suit in 50 years, moving from one habitat to another.

But should I be lucky enough to live that long, I'm sure I'll be complaining about us doing exactly that.

Alexa

Oh my gosh, that's such a good point. That's such good insight.

Emily

So we've talked a little bit about science fiction previously like Star Trek and Star Wars. Do you have any examples that you think depict a particularly good futuristic security system? Either… it could also be TV, but also in video games or books. And then also as a counterpoint, are there any examples that you think do a particularly awful job?

Schuyler

So I, you know, I was really excited for a game that unfortunately didn't wind up coming out.So this is a terrible answer. But for the two other people in the world that were excited about this thing existing, there's a game called “Hyenas” that was going to be like team heisting in space. Really like borrowing from the genre expectations of both of those things that looked like it was going to be really fascinating. Unfortunately, it got shelved so we didn't get to see what the end result was.

But in truth, I personally...haven't seen a ton of space exploration entry that I found super interesting. The ways in which we maybe use it to tell a story I think is phenomenal.

In classics like 2001 and trying to find ways in which to create human spaces of privacy while shutting out a computer that has control of the physical and secure spaces, finding the little pod to have a conversation with only to be found out that your lips are being read by the computer, so on and so forth.

Like I actually think they do some really amazing things with what security and trying to create security and create privacy and all of that. Like I think that's really beautifully done and really tense and incredible in 2001.

But as far as like depictions of a really cool lock, or depictions of overcoming a really cool lock or something like that…Every example I've seen is just one person throwing a computer at another computer. And it's a bummer, right? Like, yeah, it's cool when something flips out of R2-D2 and goes into another computer and unlocks a thing for somebody down the hall. That's totally cool. But also, I'm just such a huge mechanical security nerd that what I want to see is, you know, what the security technology of the other, interplanetary superpower in the galaxy is and how we have to figure out how to create human tools that can manipulate that, so on and so forth.

And there's some interesting stuff in there in hacking and in entry for sure, people coming across alien computer systems and starting to try to figure out how to engage with them. That classic scene of like, “Oh man, now I'm a 13 year old in a spaceship and I'm going to figure out what this button does, thank goodness they still have buttons,” or whatever. Or when they don't, that's even cooler, you know, when just some goo attaches itself onto your hands and then suddenly you're accidentally driving a spaceship. All that stuff is really cool.

I just...racked my brains, watched some back episodes of some things, watched a couple of movies, and there wasn't anything that really gave me that old school Rififi “I'm going to show you 10 ways to break into a safe” sort of vibe that we have from kind of mid-century American, European media. My guess would be that video games are there in places that I just haven't looked yet because they kind of have to be, right?

Because lockpicking as a mechanic is fun and it's going to be fun in space too. So I'm sure that's out there and I'm just not versed enough. And I got hyped about the wrong thing that never came out. And on the flip of it, I'm also sure there's some cool stuff in literature.

And in fact, I remember some, but I didn't dig it back up and get back into it in time. But I do remember some of my favorite parts of what were (entirely inappropriate for the age that I was reading them) books, the Stainless Steel Rat series by Harry Harrison, which are hyper-sexual James Bond-style romps through space. He does do the gadgetry, the fun trick, the tool that he got from someone, so on and so forth. There's a lot more of that in those, something that I should probably revisit. I was amazed by them as a kid, and they really did have kind of criminal version of James Bond style.

This amazing old, old, old book series called Raffles. Raffles was the name of the main character. And it was written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's brother-in-law as a criminal answer to Sherlock Holmes. And the veracity of everything that he writes is absolutely incredible. And I do feel like Harry Harrison was kind of creating the Raffles of the spacefaring era with the Stainless Steel Rat series.

But also my memories of that are from when I was yeah, 10, 11, 12 years old and definitely wishing I could skip over parts that I had to slog through that were not about space exploration and about very human exploration that I was not…

[laughter]

Emily

I'll definitely have to check out Raffles. I wasn't familiar with it…

Schuyler

I love it.

Emily

…I'm more familiar with the Arsene Lupin series by Maurice LeBlanc.

Schuyler

Yes, so Lupin, Raffles, and importantly, the film that I mentioned previously, Rififi, every one of those go back in inspiration to a French anarchist criminalist –his terms, he was an anarchist criminalist, he expressed his anarchic political ideals through criminal acts, wrote an amazing essay about it – named Marius Alexander Jacob.

And one of his signature moves was that he would rent out an apartment directly above an apartment that he either intended to rob or where he intended to like tie up the tenants of to rob something else, whatever the case may be.

What he would do is he would drill through the floor, small hole, shove an umbrella through that hole, open the umbrella up, chisel out a large enough hole while catching all of the debris in the umbrella, chisel out a large enough hole for him then to slip down into so that he could then burgle the apartment, bring it all back up with him, and be out the door. You see this played out in an extraordinary 40 minutes of silence in the film Rififi, which is absolutely incredible, so well done in Rififi that to this day, entry through the roof is called a Rififi coup.

And there was a string of Rifificoups against Best Buys in America about a decade ago, where some Best Buy employee realized that the way in which they were putting up the banners for the new Apple laptops created this perfect triangle of protection from the cameras, from the security cameras, so they would go onto the roof. And because it was the same at every Best Buy, because it's a big box retailer and the layout is the same every time, they would go roof to roof to roof, inserting themselves at the exact same point between these three banners, steal all of the MacBooks and go on their merry way, carrying out the biggest series of Rififi coups in all time. But all of it goes back to Marius Alexander Jacob, the French anarchist criminalist that inspired Lupin, Raffles, and Rififi.

Emily

While you were talking about the biometric potentials of wearing a suit and making sure that the right person is wearing the suit to get into the system. It reminded me of the game, the computer game “Among Us”...

Schuyler

Yes!

Emily

…that I played with my brothers like during the pandemic.

Schuyler

That's actually very interesting.

Emily

Because you look the same as the killer, it's entirely more on the social contract of doing it more sneakily, like your story versus the 11 year old

[laughter]

Emily

and underwater lockpicking. I was not very good at it because I didn't realize…I could be sneaky, but I didn't realize that only the murderer can go through like the air vents or something.

[laughter]

Emily

And so I did it very…I actually, I think I almost got away with the crime. And then I very confidently [laughter] just went through the air vent in front of everyone assembled around the body.

[laughter]

Schuyler

Perfect. [laughs] perfect. It's so good.

Emily

And I didn't realize that was a capability that only the killer had of circumventing all of the security.

[laughter]

Emily

And then I think also in terms of talking about locks, we actually haven't really touched on it, but just the terminology of an airlock.

Schuyler

Yeah, for sure.

Emily

Going back to “Among Us,” because obviously when you're captured, as I was, blatantly.

Schuyler

You get airlocked.

Emily

Yeah, you just get thrown out the airlock. Because that's the only thing I can think of. But even then, it relies mainly on the social contract aspect of trying to killing someone and getting away with it.

Schuyler

I don't know if it was myself or my wife, but one of us did the exact same thing when, yeah, playing pandemic era with friends. When you eventually get a space linguist on, for me, find out from them what the opposite of a shibboleth is. The thing that someone says, then everyone's like, “No, you're a murderer.” [laughter]

Because I want to know what that is, because that's what you did. [laughter]

Alexa

Shibboleth revoked…

[laughter]

Emily

Redacted.

Alexa

redacted. [laughter]

Well, I think we could sit here and ask you questions and learn about security and locks and space probably for a good six more hours. As we wind down, though, I do want to ask a little bit about, if you are comfortable talking about whatever you're working on at the moment, if you have any projects coming up that you're excited about that you'd like to mention before we go.

Schuyler

Yeah, totally. Honestly, there isn't anything specific on the horizon. The big thing is that I keep going with one research project in particular. And right now I'm collaborating with this dope high school student in Chicago, actually, who's been working to create 3D models and 3D print some of those patent models that we lost in the Patent Office Fire of 1836.

So this is work that I've been doing for more than a decade now. It's before I got married that I launched the project, call it the X-Locks project.

Somebody had managed to make a catalog of the names of all of the lost patents. When the Patent Office fire happened, we only managed to recover maybe 30% of the paper knowledge and none of the patent models whatsoever from that time.

And that initial 30% recovery happened soon after the fire had actually happened, soon after 1836 when the creators were still alive, when people could submit fresh papers, copies that they had received themselves, whatever the case may be and then things stagnated. And every now and then you'll see like an amazing find. Somebody finds a patent, then is able to restore it to the patent record.

And over the course of the last however many years, I have found myself and a couple of folks who've helped me with transcription work in particular, have managed to recover a bunch of really cool stuff. Some of it the full letters patent for the security-related patents, some of it drawings right before I'll say things got incredibly complicated with communicating with folks at the National Archives. I was lucky enough to have the historian at the US Patent Office and some incredible people at National Archives offices in Kansas City and in DC help me track down much higher quality art of some of the lost patents that we had lost.

So there have been some really cool recent gains that have finally brought together some of these transcriptions and art in such a way that I can confidently say, this team of brothers invented this not great, but kind of cool lock with one really good idea in it. And then through some friends and connections, found somebody that was interested in having one of their students do an independent study, helping me turn this into a physical reality.

And that was one of my goals from when I first set out on this X-Locks project was in this ash, there's this incredible amount of lost cultural mechanical knowledge. And wouldn't it be amazing, 200 years on from this event, to hold one of these little pieces of genius in your hand?

So I'm so excited for the work that he's doing. This is going to be the first time for this patent specifically, this is the Campbell patent, it'll be the first time in over 200 years that anybody has made this lock, which is so exciting. I'm incredibly excited to have a physical copy of this thing in my hand. So the X-Locks project continues. This will be a really exciting sort of close of a chapter, so I'll definitely be writing about it. Where it'll wind up, goodness knows. But in general, I just love this stuff.

So yeah, if anybody ever wants to talk about locks, I'm not always the most consistent correspondent, but wow, you know, you invite me on a podcast and I can just be asked questions and ruminate on locks for a couple of hours. Yeah, there you go. That's my pitch. You have a podcast? Invite me to talk about locks. How's that?

Emily

Absolutely. Be careful. You'll be asked back for another episode.

[laughter]

Schuyler

It would be my pleasure. I'll reread all my Harry Harrison and finally still playing some video games again.

[laughter]

Emily

Do you have any advice for people interested in lockpicking or in the history of security?

Schuyler

Yeah, for sure. For lockpicking, I mean, YouTube's just become extraordinary at this point. For folks that don't like doing that sort of work via video but prefer textual references, I would actually still kind of point you in the direction of those same creators. A ton of amazing people on YouTube. Bosnian Bill is one of my favorite human beings in the world and is well known, just incredibly kind-hearted dude with some really clever ideas about how you teach this sort of stuff. So any of his work, but there's a ton of people in that community.

And then when it comes to the history, especially if you like it tied to that lock picking, there's a guy that goes by the name Artichoke. And on my own YouTube channel, I was so taken, just so completely enamored by the incredible deep dives that he does into manufacturers, into like the incredible specific nitty gritty of some really niche high security lock picking, but not just how to do it, but like the history of the company that did it and the lawsuit that changed the lock and so on and so forth.

And just like, so if you're anything like me, if you're listening to me and thinking this is a good way to be and love you if you do, his work, I would recommend you check out ArtichokeTwoThousand on YouTube. He truly just does such incredible deep dives on all of it.

Obviously my stuff is out there. My name is Schuyler Towne. I'm sure the funky spelling of it is in the episode title and description and whatnot. I've got a lot of stuff out there. I've got stuff that doesn't exist anymore. So again, I mean, if you want to learn more about the history of security technologies, you just have to have me on your podcast, I guess. I'm so sorry.

[laughter]

Alexa

Amazing. And I assume you're also on social media?

Schuyler

Yeah, BlueSky. I think I'm Mr. Towne in Blue Sky, Mr. Towne. There's an E at the end of it. And yeah, hit me up. I really do love talking locks, talking security, talking how human beings are so inherently tied to the security technology. Yeah, that's my jam.

Emily

Fantastic, Schuyler. Thank you so much for chatting with us this evening. This has been so lovely!

Schuyler

Thank you both so much. And thank you so much for making it work. I'm excited.

[interlude music - “Space” by Music Unlimited]

Emily

And to our listeners, thank you for joining us for this episode. If you like what you hear, please consider rating or leaving us a review on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you listen to the show. This helps spread the word on those platforms.

Alexa

And if you think other folks in your life would enjoy conversations like these, feel free to share with friends and loved ones! All of our show notes, links to guest content, and episode transcripts are available on our website at www.artastra.space, and we’re also on socials at ArtAstraPodcast.